This was the era when the tones of Bunny Berigan’s record of ‘I Can’t Get Started’ seemed to come floating out of every window between Beaumont Street and Wellington Square (Kingsley Amis, Memoirs 1991 p.48)

Kingsley was writing of 1941 and 1942 in wartime Oxford. At the same time that the students were putting off thoughts of call-up with whatever records Acott’s had and whatever beer the Gardener’s Arms could supply, Bunny Berigan lay dying. He was 33 years old.

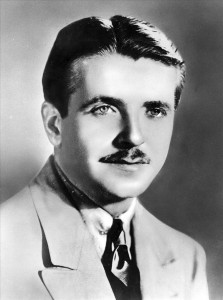

In every photograph we have of Berigan, he appears older. He has the facial set and incipient jowls of a man in his mid-40s, and his young man’s moustache looks like the left-over style choice he can’t quite bring himself to change. Something about his hair that even Brylcreem can’t quite hide gives the game away. Berigan died after two sizeable drink-induced heart attacks. He had already been diagnosed with cirrhosis of the liver.

Like his fellow white late-1930s jazzmen, Berigan made his name in the era of swing that followed the repeal of Prohibition in the United States. He’d worked in one of Glenn Miller’s early bands, then more successfully with Benny Goodman. I Can’t Get Started is a lovely, languorous record, reprising Cole Porter’s “list” songs with gentle melancholy, but with Goodman he produced other, more energetic music.

What fun it all sounds: tanking about in American automobiles with giant engines and no brakes from studio to ballroom, with all the dames and booze and untipped cigarettes you could wish for, at night, surrounded by Art Deco. Sunset parties on Long Island: in the imagination, a green lamp draws you from the end of a dock, and a voice whispers, “Gatsby.”

What can it have been like? We could have found out. Because, in the early 1970s, the British invented the Time Machine. (Did we tell you? Perhaps we didn’t.) As Kingsley Amis relates in his short stories The 2003 Claret and The Friends of Plonk, the UK government of the day was sufficiently unmoved by this technological windfall to park the device with a harmless, underemployed corner of the Home Civil Service.

It sat there neglected for a while, until its bored guardians, time hanging on their hands, put it to use with successive expeditions exploring the past and future of their favourite alcoholic drinks. Britain in 2010, they discovered, would be a dystopia of terrible pubs and appalling beer. Medieval French wine, on the other hand, was ambrosial.

Get yourself another crystal ball Margaret Thatcher told Amis some years later. She wasn’t entirely wrong: there are pitfalls and dangers in extrapolating the future from everything you dislike about the present. But Amis’s civil servants had a point. Who hasn’t wondered at some time how food and drink tasted in the past, or how it might in the future?

And again there’s that whispered word “Gatsby” and the green lamp at the end of the dock. “I’ve been drunk for about a week now, and I thought it might sober me up to sit in a library” (F. Scott Fitzgerald The Great Gatsby 1925 ch.3). The music drifting through the windows into that library, of course,would have been that of Bix Beiderbecke – but those might have been his words, too, and his form the one slumped there amongst the shelves. And what about the drinks that lost week – the drinks at those magical parties on the lawn during those long purple evenings in the New World? Prohibition came in in 1919 when Bix was 16 years old: when the incoming Democrats called time on it in 1933, he’d been dead two years already. But what beauty in the meantime. I’m Coming Virginia is the high point of white jazz – and one of the great jazz moments of any kind.

“Beiderbecke’s ideal biographer might have been Scott Fitzgerald, who would have retained the romance of his career while recognizing the tragedy of his character” said Philip Larkin in an interview1 for the Guardian in 1965. Beiderbecke was too gentle, too polite, to refuse: by his death in 1931 aged 28 he was on three bottles of bathtub gin a day. What did the drink at Gatsby’s parties taste like? Like fruit juice and petrol: and the parties themselves, in reality, were as rumpled as this photo –

– which is as good as images of Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda get. After Scott Fitzgerald’s drink-accelerated death in 1940, at the age of 44, his friend Edmund Wilson pulled together his final essays in a book called The Crack Up after the 1935 piece of that name.

Scott Fitzgerald’s way with writing, and the jazz of Bix and Bunny, and that kind of drinking life, turned out to be young men’s games. There was, in the end, no need for that British Time Machine. Scott Fitzgerald’s novels had warned us already where that kind of nascent celebrity life would take us, to – as Clive James said in Cultural Amnesia – “a dead body floating in the swimming pool.”

1Larkin interview: Poet on the 8:15: interview with Philip Larkin by J.Horder, Guardian, 20 May 1965, 9

I suspect that white jazz – indeed all jazz – had several high points: it’s a spikey business.

Here’s an earlier one.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ATJjP3Dzsfw

I’ve been trying to think of a tune that sounds as if it was written to represent drunkeness. There’s a case for Jada.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gI9g1uW1IEs&feature=endscreen

Thanks Bill – both of these just lovely.