It’s true to say that the United Kingdom never really threw itself into sound recording experiments with the gusto of the United States, but nonetheless there are some fascinating survivals, and we’re going to showcase five of them here. They encompass government, domesticity, transport, street soundscapes and industrialization and each has its own story to tell and inspires its own reflections. Taken to their logical conclusion, any such reflections will end up being – reluctantly, inevitably – about death. Sound recording has the same ability as colour photography and colour film to strip away the superficial differences between ourselves and the distant past. With those differences eroded, what’s left is an experience of normality, even banality, being undergone by the dead with the same mundane indifference we bring to it, and what that means for us “Brings the priest and the doctor/In their long coats/Running over the fields.”1

Big Ben – 1890

http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/bigben.mp3

This may well be the earliest sound recording made outside in the United Kingdom. As you can see from the photograph of Westminster Bridge above, the roads around the Clock Tower were busy: the noise generated by a succession of iron-tyred vehicles and iron-shod horses must have been considerable. The absence (regrettable absence) of any such street soundscape here indicates that the recording was probably made from a boat, specifically to avoid picking up traffic sounds. Traffic noise was a considerable problem to the Victorians in London: Chelsea Vestry reports contain entries detailing schemes to resurface roads outside hotels and hospitals with wood, felt or rubber, all in the hope of tamping the racket down. Tarmacadam wouldn’t be invented until about 1904, and then by accident.

In 1890, Big Ben was a mere 32 years old. That much time and more would pass again before the bell’s chimes on the hour became a symbol of European freedom when broadcast by the BBC during World War II: what the Victorians made of it and associated with it is harder to know. A symbol of success? Of rebirth (the fire which destroyed the Palace of Westminster in 1832 was just still within living memory)? Of progress – symbol of the era in which Britain became the premier world power, an unprecedented industrial innovator and a model of national self-improvement? Of the future? Kipling’s Recessional was still seven years from being written, and its mix of astonished self-satisfaction and needling fear would strike a chord on its publication. And to whom? Kingsway was as yet unbuilt, and the slums around Covent Garden and Holborn contained people in their thousands for whom Big Ben and the Clock Tower might have had any number of alternative meanings.

Lionel Mapleson at Home in New York, February/March 1902

Lionel Mapleson was born in London, the son of Queen Victoria’s librarian, but like many forward-looking British men of the middle and lower classes, sought his fortune in the United States, which as the century turned was beginning to solidify its position as the country of the future. Beginning in 1901 with a Thomas Edison Home Phonograph, Mapleson used his position as librarian at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House to gain access to performers and to experiment with capturing performances on phonograph cylinders. Initially these recordings were made from the prompter’s box, but by 1902 he had installed a Bettini cylinder recorder up in the “flies” and it is from here that he made what are unique soundscapes of a full opera house and orchestra in full flow before World War One.

This is interesting enough, but cylinders could be reused, and on at least one occasion Mapleson took a cylinder home and recorded his own family life. Here’s one example. The recording begins with an excerpt from an unexceptional opera, Manru by Paderewski; but that fades out, and we find ourselves in the front room chez Mapleson where the pater familias is entertaining his children:

http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Manru.mp3

This must surely be one of the only true recordings of an Edwardian/Gilded Age domestic setting. Until the arrival of the home video camera in the 1980s, such things remained few and far between in British families at home or abroad. My own family taped Christmas Day 1974 on a little mono radio-cassette player, and that C-60 contained the only recording ever made of my grandmother’s voice (the only grandparent who survived into my lifetime). Now lost, of course, but I remember that I was in the background somewhere, banging a drumkit. With the Mapleson recording, what strikes you is just what a modern man Mapleson was. There is no trace of the authoritarian Victorian father here, if such men ever really existed. Instead, we find ourselves in the presence of an urbane, cheerful and witty man in his mid-30s. Other than the date on the cylinder and the state of the recording, there is little in his manner or his children’s that might exclude them from any decade of the twentieth century. And in twelve year’s time, of course, World War One will arrive, and Britain first, then America, will pitch almost every one of its Maplesons into the iron storm of the trenches. The Great War is easier to bear as an event if you can imagine it fought exclusively by the satirized schoolboys and Tommies of Blackadder Goes Forth, but as Lewis-Stempel’s Six Weeks and this recording makes obvious, the truth is altogether more vicious and closer to home.

Victoria Coach Station, London 1935

This is one of a reasonably large number of BBC recordings made by, amongst others, H. Lynton Fletcher, and to my mind it is amongst the most interesting. Lynton Fletcher had a sense that transport soundscapes mattered – here’s his 20 January 1936 radio broadcast, Some Famous Trains , which captures London railway termini such as Euston. Our contemporary Beeb is eager to label this kind of work as “hailing” from a “bygone” era, but if the recordings indicate anything, it’s that the “era” is nowhere near as “bygone” as you might like to think:

http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Victoria1935.mp3

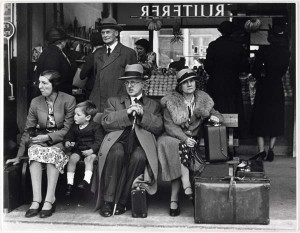

Victoria Coach Station was still very much a novelty when the recording was made – as was the inter-city coach travel it facilitated. The Art Deco station was restored in the 1990s, but had kept its original 1932 interior form – basic and unsafe to modern eyes – right up until the end of the 1980s. It became something of a crime blackspot for a time: I remember admiring the British sang froid of a worker there who steered his ride-upon vacuum sweeper vehicle right through the middle of a large gang knife fight that was going on outside my coach window in the early hours of a 1991 weekend. Then, drivers and coach station guides still called out the destinations just as they had done 55 years earlier, and this is what strikes home for me from this recording: not what has changed, but what hasn’t. How many of those men, deep into the normality and mundane routine of their ordinary day, would within the life of a single parliament lie dead for the sake of Hitler’s mad ambitions? And that normality and mundane routine stretched away from the 1935 coach station, out of earshot, over land and sea to encompass millions, leaning perhaps for a compensatory cigarette at that moment but unaware of the unimaginable things closing rapidly in that would quickly evaporate everything familiar and dear to them. These things aren’t history, and they don’t happen to paper figures in black and white photographs, but to us, or to people who are so like us as to make no difference.

A shopping street in York and a back garden in Newcastle, 1947

These 1947 “Home Flash” recordings have been used by the British Library SoundMap project to compare the volume of modern streets with those our grandparents knew – they came to the conclusion, surprising, surprisingly, to some, that the twenty-first century city is a quieter place than its Attlee administration predecessor. But it shouldn’t be a shock. The York street in 1947 is full of two-stroke engines and vehicles powered by diesel like the trucks my step-grandfather drove for forty years. It must be remembered how sudden and complete motorization of British society was. The first truly practical petrol and diesel vehicles emerged from the Great War, during which power and ease of maintenance had become huge priorities overnight. Within twenty years, bypasses and inner-city highways were being planned, even in relatively sleepy places like Oxford where the infamous “Merton Mall” came within an inch of destroying the world famous views across Christ Church Meadow. Thus came to an end countless millenia of horse-drawn transport in our towns and cities, and the psychological impact of that shift in mode, speed and space has yet to be fully explored. A child growing up in a street smelling of a mixture of coalsmoke and horse manure would, by early middle age, have become entirely accustomed to the powerful blue exhaust smoke and its contrasting, overwhelming, unmistakeable perfume:

http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/York1947.mp3

Our final recording, another 1947 “Home Flash” production, is more peaceful. It was originally titled “Newcastle Sparrows”, because these little birds once dominated British suburban gardens of the kind captured here. Their numbers have collapsed since the 1980s, and a once familiar sound has now become something heard only on Greek and Italian holidays.

But although this is a garden recording, it’s also a recording of Newcastle – one of the great cities of the British industrial revolution. If you listen carefully, there’s a hum on the air:

http://www.garreteer.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Newcastlegarden1947.mp3

That hum is the greatest lost British sound of them all: urban industry at work. We are lucky to have this at all: in 1947, British industry was enjoying its brief war-and-postwar respite from the decline and decay which began after the Great War and which had J.B.Priestley so worried on his 1934 English Journey. It wouldn’t last long, and after 1979 what little was left came under the purview of politicians who knew nothing about manufacturing and cared even less. Now all we have left to hear are Flymos and strimmers.

1Philip Larkin “Days” The Whitsun Weddings

Very amusing. Lionel was my great-grandfather.