(Anyone with the slightest interest in Kipling will enjoy Mathew Lyons’ two pieces at Normblog: Mathew Lyons on ‘Kipling and His Critics’ and Mathew Lyons on The Jungle Book by Rudyard Kipling . Much more Lyons via his excellent and recommended Twitter feed.)

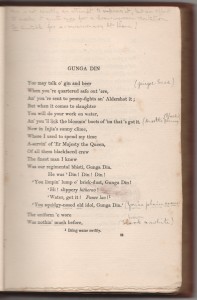

Perhaps they thought it reduced the value, because I picked it up for a couple of pounds, but I wouldn’t have looked twice but for the note of horror in the  comment pencilled in at the front - Gunga Din Bowdlerized! Now, there’s a headline. And it doesn’t exaggerate. But I’ve come to think that there might be more to it than Shelter in Raeburn Place seem to have thought.

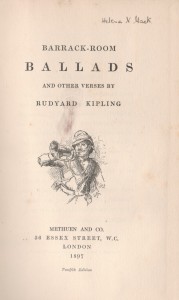

Helen N. Mack – whose name is on the title page above – isn’t hard to trace. She was born in the early summer of 1880, the fourth child of her family, and very shortly afterwards moved from her Southampton birthplace to Knole Road, Sevenoaks, a few yards from the Sackville-West calendar house. She never married, and died in 1961 having spent her entire life in the vicinity of the South Downs.

There’s every sign that this edition of Barrack Room Ballads came into her possession when she was a young woman, and that its acquisition wasn’t accidental: she’s added another (still) uncollected Kipling poem, “The Bushman’s Daughter” in her own hand at the back of the book. It’s an interesting choice – Kipling isn’t widely known for his anti-British, anti-imperial, anti-racist verse, yet here’s a perfect example of just that. The Daughter of the poem is ten, and is hauled up in front of our good British justice for some trifle. She gets three weeks in gaol and five years in “felon school”, and the poem concludes:

Oh, this is the law and the Peterboro’ law On a tricky little elf of ten, And the Lord be thanked we are Hottentots Instead of Englishmen. ÂIt would be interesting to know where she found this: had it been reprinted as a miscellaneous poem in some other collection for Helena to copy across? It’s first appearance had been almost a decade earlier, in the St James Gazzette of 1890, but whatever note it rang then, its echo surely would have changed utterly during the Boer War during which the nation’s poets sought to bolster, by and large, the Empire, rather than call it into question.

Helena’s hand is not the only one in the book. There’s a second, anonymous hand, a hand that has chosen to paste an interesting pair of extra poems into the front of the book.

The first of these is Kipling’s Absent-Minded Beggar, written to fund relief for Boer War troops and an instant hit following its Daily Mail publication on Hallowe’en 1899 and its setting to music by Arthur Sullivan. Here, the poem has been handwritten onto thick, creamy paper which has the verse numbers preprinted on it in Roman numerals. Something has been printed on the gummed side: frustratingly, the only text I’ve been able to decipher reads ..in the Daily Mail.. which takes us no further.

Pasted next to the poem is Sir Owen Seaman’s 1899 Punch sendup of Absent-Minded Beggar, written in the Latinate style of Alfred Austin, the notoriously pompous and talentless successor to Tennyson as Poet Laureate. Seaman would go on to become one of the great Punch editors of the magazine’s last good years. He had it in for Austin, never neglecting a chance to remind the world that Austin’s laureateship had everything to do with his close friendship with Prime Minister Salisbury and little to do with anything else.

Juxtaposing the poem and its satirical cousin indicates an awareness at some level of Kipling’s style. Beggar, like the Barrack-Room Ballads, owed much to music hall and Kipling’s enthused discovery there that he could put his knack for soldier’s language to use in a way English poetry hadn’t attempted much before. (The obvious comparison is between Kipling and William Barnes, but Barnes was interested in dialect and Kipling was interested in slang and social status, different things altogether). Where Helena Mack’s Kipling choices betrayed a sympathy beyond race and nationality, a suspicion of the status quo, the choices made by the anonymous hand are more mischievous and knowing: here was someone who enjoyed wordplay and the pricking of bubbles. Here’s a bit of Kipling and Seaman/Austin compared:

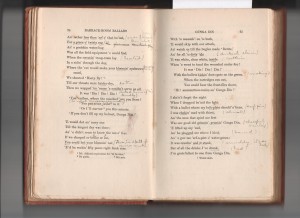

When you’ve shouted “Rule Britannia” – when you’ve sung “God Save The Queen” – When you’ve finished killing Kruger with your mouth – (KIPLING) Â Â When ‘Rule Britannia’ rings through hut and hall, And men have sung ‘God Save the Queen’ withal; When has been whet the keen invective’s sword Against Meridian Afric’s tyrant lord; (SEAMAN/AUSTIN) ÂIt’s the anonymous hand that has a crack at the Gunga:

It’s interesting that the writer explains themselves at the top of the page. Bowdlerizers aren’t known for suspecting their own motives or for being burdened by the desire to justify themselves. The writer expects other readers to pass by who might disagree with what’s been done. And we can trace some sarcasm here, surely:

This is not an attempt to improve it, but an effort to make it quite nice for a drawing-room recitation. So suitable for a missionary At Home!

A missionary link might explain Helena Mack’s feeling for The Bushman’s Daughter – but not the bowdlerizing of Gunga Din. And as you’ll see from the remaining pages below, the thrust of the “corrections” isn’t the desire to push back against obscenity or paganism, but to reimagine the poem as told by an elegantly-spoken gentleman officer or regimental padre. This might not be the work of a Kipling critic – and there’s little sign that the language of Barrack-Room Ballads excited any outrage about its use of language – but instead that of a thoroughgoing fan, one who so enjoyed Sir Owen Seaman’s pro-Kipling satirical stance that they wanted to try it for themselves at home. If there was to be a missionary at the receiving end, then that missionary would have to have been in on the joke. That, or the Mack family despised missionaries tout court. And there’s something about the hateful, smug references to watching Gunga Din burn from the safety of heaven at the end that suggests it’s the latter.